By Lyman H. Reynolds, Jr., Esquire - Roberts, Reynolds, Bedard & Tuzzio, PLLC

Discrimination is a comparative concept. It requires an assessment of whether “like” (or different) people or things are being treated “differently.” “Discrimination consists of treating like cases differently.” 1 Likewise, treating different cases differently is not discriminatory. A comparator is the person or persons (or in some cases, businesses or properties) that the plaintiff asserts is just like them. The concept of the comparator exists in several types of cases, such as employment discrimination, civil rights (including Title VII and 42 U.S.C. § 1983 claims), housing, disability and equal protection claims.

“Comparators” are no different than those you might encounter in your daily lives. Who has not scrutinized two or three or four cars when shopping for a new vehicle? How many times have you likened someone you know to a celebrity, only to qualify that statement with, “but they have better hair than you do”?

In practice, from the plaintiff’s perspective, they have been discriminated against and the comparators have not, even though there is not a good reason for the difference in treatment, which is why there is a complaint or lawsuit in the first instance.

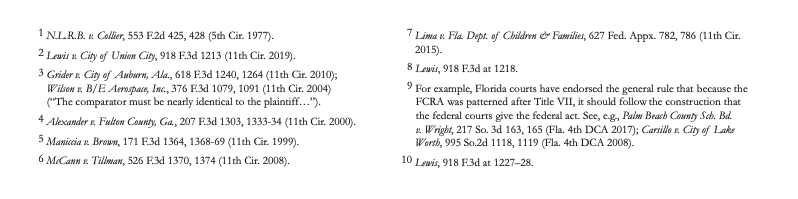

However, this begs the question: just how similar must the comparator be to the plaintiff? As the Eleventh Circuit has recently stated, “our attempts to answer that question have only sown confusion.” 2 In some instances, the standard has been “prima facie identical in all relevant respects.”3 In others, “identical” comparators are not required, but merely “‘similar’ [alleged] misconduct from the similarly situated comparator.” 4 Under that more forgiving standard, “the quantity and quality of the comparator’s misconduct [must] be nearly identical.” 5 Yet “‘nearly identical’ does not mean ‘exactly identical.’” 6 In other contexts, the plaintiff must show that the comparator’s responsibilities “are equal in terms of skill, effort, and responsibility[.]7

Recently, the Eleventh Circuit issued an en banc (the full court) opinion in Lewis v. City of Union City, 15- 11362 (11th Cir. 2019), seeks to establish a single workable standard for what level of similarity must exist for a comparator to be a valid comparison to the plaintiff. Lewis sets the “new” standard as: “[W]e conclude that a plaintiff asserting an intentional-discrimination claim…must demonstrate that she and her proffered comparators were “similarly situated in all material respects.”8 Although Lewis is an employment discrimination case, the Court indicated that this standard would apply to all federal discrimination claims. Indeed, it is likely that Lewis will even have influence on Florida state courts’ future rulings since the state civil rights statutes mostly adopt the federal jurisprudence of similar statutory claims.9

So, what does the standard or “similarly situated in all material respects” mean in practical application? Anticipating this discussion, the Court enumerated several “guideposts” in for application. Under this standard, to be a similarly situated the comparator should have “engaged in the same basic conduct (or misconduct) as the plaintiff, will have been subject to the same policy, guideline, or rule as the plaintiff, will ordinarily (although not invariably) have been under the jurisdiction of supervision, and (in the employment context) have the same employment or disciplinary history[.]”10 As the Court further explained, “[A]s its label indicates, a valid comparison will turn not on formal labels, but rather on substantive likenesses. [A] plaintiff and her comparators must be sufficiently similar, in an objective sense, that they ‘cannot reasonably be distinguished.’”

How much has really changed under this new standard? In Lewis the plaintiff, an African-American woman, sued the City of Union City over the application of a new policy at the City’s police department regarding the use of tasers.

All officers who were required to carry tasers were required to undergo a 5-second taser shock as a part of training. Lewis declined to be tased since her doctor recommended against it due to her heart attack two years prior. Lewis was then placed on unpaid administrative leave until such time as her doctor released her to return to full and active duty. Lewis exhausted her accrued leave but did not complete the necessary FMLA paperwork to proceed with unpaid leave. She was then terminated as being unfit to work under the City personnel policy.

Lewis alleged that her firing was harsher treatment than her comparators received. The first comparator was a white man who failed the “balance” portion of a physical-fitness test and was given 90 days of unpaid administrative leave to remedy the conditions that caused him to fail. He later retook and passed the test within the 90-day period and returned to work. The second was a white man who failed an “agility” test and was also placed on unpaid administrative leave for 90 days. He was offered and ultimately declined a different position, but in the end, he was terminated after 449 days on unpaid administrative leave after negotiations with the City regarding his disability status failed.

The full Eleventh Circuit, in reversing the panel decision to the contrary (and subject to a 68 page dissent) that Lewis’ comparators were not “similarly situated in all material respects.” Lewis and her alleged comparators were not placed on leave pursuant to the same policy provision. They were not disciplined in temporal proximity, since Lewis had been disciplined years earlier. Finally, the conditions underlying their leave were not similar enough.

In practice, “similarly situated in all material respects” appears to slightly relax the standard for a plaintiff but still largely favors the employer / governmental entity defendant. The plain language of the new standard reduces the plaintiff’s burden in one aspect in that the comparators do not have to be “identical” in all respects. However, requiring that the comparators be “similarly situated in all material respects” —but raises the burden in another— from “relevant” to “material” respects. It is worth noting that, as the facts were presented in the opinion, Lewis did not seem to be a particularly close case because there were several obvious differences between Lewis and the comparators such that her case would likely have failed anyhow. Still, now that the Eleventh Circuit has reset the comparator standard, governmental entities and employers should incorporate the new language into their decision-making processes, and practitioners should be aware of the change in order to present their arguments in the strongest light.